Between Baroque and the Commie Block

When I was a child, I stood with my dad in front of the place where he grew up. In my mind, it looked like a solid concrete block rising four or five floors from the ground, and looked very little like any of the other old buildings around it. Built during the times of socialist Yugoslavia, it was a tenement exhausted by decades of post-war hangover and deflated dreams of a different future that the region hasn’t truly ever recovered from. The building was stained by weather and time, and its sharp edges didn’t really inspire much joy in me. I told him it looked ugly. My dad laughed, looked at me, and said something along the lines of “It may look ugly to you, but this really was the future when I was your age”.

Coming from Eastern Europe, more than once have I heard and read people describing cities there as a hellscape of repetitive grey concrete block-housing. What some people like to derogatorily call ‚Commie Blocks‘. This is true, to some extent, and its hard to argue against reality when so many of our cities are marked by row upon row upon row of nearly identical looking grey tenements. This is often tied to follow up statements when people visit the old-towns of quaint European cities, looking upon beautiful buildings from the 18th, 19th, and early 20th century, and remarking „why don‘t we do this anymore?“.

Well, I will be honest, I do much prefer the adornments, colour, and artistic quality of many old-town buildings. They are attractions in-of-themselves for a reason. I love to walk around the central districts of cities like Vienna, Zagreb, Budapest, and Rome, where it seems that every side-street is home to some architectural masterpiece that amazes me every single time. I‘m no expert in architecture, which is why I studied urban planning instead, so I won‘t try to act as if I know the correct words for them - but there is something lovely about the ‚twirly-wirly‘ design of Baroque and Neoclassical buildings. Its exciting, colourful, and wonderful to look at. You can turn down any street and find a little cherub staring down at you from a balcony.

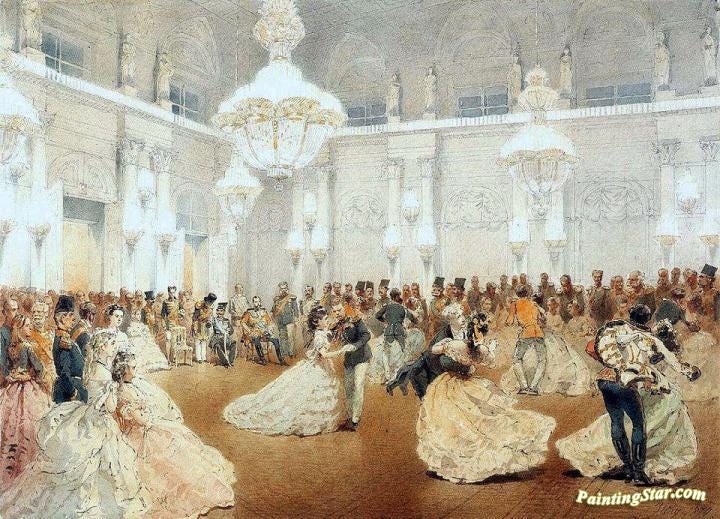

But, this is where we ruin the fun. Many of these buildings, especially the ones that look awfully like they used to be mansions, or still literally are palaces, have some skeletons in their closet. Vienna’s city centre is punctuated by the massive and impressive Hofburg Palace, and its always great to walk past it. Its now home to the President of Austria and a neat little museum, but for hundreds of years it was the seat of the Habsburg dynasty, the rulers of empires (yes, multiple empires) that brutally exploited millions across the globe. You see, the issue is, many ‘fancy’ old European buildings were funded either directly or indirectly with money gained from exploitation and extraction, and were designed with the specific intent to project wealth, status and power, the gaudier the better, to both catch eyes as well as to show “look, I will, without a second thought, spend money you won’t ever see in ten lifetimes to deck-out my halls in gold”. Buildings and urban spaces are as much symbolic as they are practical.

So, what does any of this have to do with social housing, modernism, and brutalism? To begin, lets tie these three things back to what I said about wealth, status and power. Architecture and urban planning are not value-free, and what I mean by that is that they are not a-political, or that they just look to build the prettiest house and design the most efficient city. Instead, these two fields have been a fundamental tool with which those in power shape the world around them. With wealth comes power, and with power comes the ability to remould the physical space around you to your own benefit and to the detriment of others. What buildings such as the Versailles, the Hofburg, and the Winter Palace have in common is that they were huge, blinding, and imposing displays of grandeur, meant to intimidate and separate.

Then, came a new wave of architecture and planning that flooded in after many of Europe’s monarchies were swept away in the 19th and 20th centuries. It was a violent rebellion against the past, against a world that revolved around wealth, exploitation, blood-ties, and increasingly extreme displays of wealth. A new world was offered, ambitiously, by a new generation of architects and planners, one built on redistributing the benefits of the city equally to all.

What emerged was complicated, to say the least. There is plenty to criticise about the authoritarian-nature of many of the socialist states that emerged in the early to mid 20th century, and I certainly will not be defending them, but it is difficult not to admire what was attempted and, I would argue, achieved when it comes to reshaping our cities - for better and worse (because nothing is ever so simple in life). The societal transformations during this time was unprecedented, dragging states that were for so long relegated to afterthoughts in the mind of the Western world to a position of equals. The past was killed and a new future was built.

This, I believe, provides some crucial context to Brutalist and Modernist architecture in many parts of the world during the tumultuous 20th century. Today we gaze in awe at the beauty of 18th and 19th century architecture here in Europe, and we all too easily look down on a style of building and designing that offered a new world. What we see as gorgeous, colourful, and stylish not too long ago represented exploitation, oppression, and exclusion. What we see today as grey, sharp, and hard was once a radical experiment that offered a break from the past. Brutalism, Modernism, and the states that indulged in it themselves are loaded with criticism, plenty of which can be made. I am not the biggest fan of the architectural style itself, nor the rationalist and technocratic planning approach often behind it.

But, remembering what my dad told me about the tenement block he grew up in shifted something within me. It was the future to him. To a people who at the time grew up in near-feudalist conditions, in areas barely noticed by the world, it must have been almost wonderous to be a part of a new future, one not tied to the symbols of a oppressive past. A little kernel of history goes a long way in understanding the built environment around us. You can hold your opinions on style, function, form, symbolism etc., but you must also appreciate the context within which a space was made. Maybe then we can be more critical of what we are quick to adore, and more understanding of the things society so easily denigrates.

That’s the beauty, or the tragedy, of cities. We can see layers of dreams stacked on top of one another or squeezed shoulder to shoulder, made real in brick and mortar, and all too quickly forgotten and misunderstood.